Bacterial Conjugation Definition

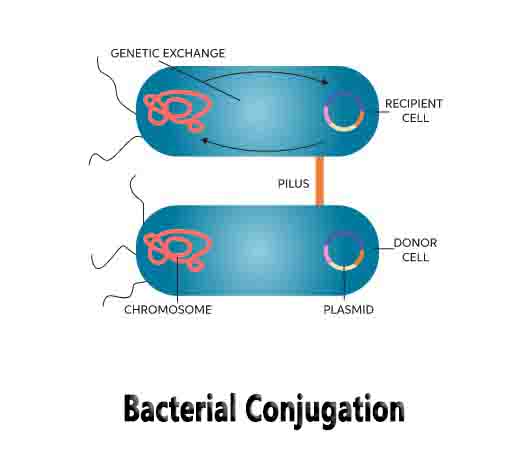

Bacterial conjugation is a way by which a bacterial cell transfers genetic material to another bacterial cell. The genetic material that is transferred through bacterial conjugation is a small plasmid, known as F-plasmid (F for fertility factor), that carries genetic information different from that which is already present in the chromosomes of the bacterial cell. In fact, the F-plasmid can replicate in the cytoplasm separately from the bacterial chromosome.

A cell that already has a copy of the F-plasmid is called an F-positive, F-plus or F+ cell, and is considered a donor cell, while a cell that does not have a copy of the F-plasmid is called an F-negative, F-minus or F– cell, and is considered a recipient cell.

The transfer of the F-plasmid takes place through a horizontal connection by which the donor cell and the recipient cell directly contact each other or form a bridge between the two through which the genetic material is transferred.

In cases where the F-plasmid of a donor cell has been integrated in the cell’s genome (i.e., in the chromosome), a part of the chromosomal DNA may also be transferred to the recipient cell together with the F-plasmid.

Bacterial Conjugation Steps

In order to transfer the F-plasmid, a donor cell and a recipient cell must first establish contact. At this point, when the cells establish contact, the F-plasmid in the donor cell is a double-stranded DNA molecule that forms a circular structure. The following steps allow the transfer of the F-plasmid from one bacterial cell to another:

Step 1

The F+ (donor) cell produces the pilus, which is a structure that projects out of the cell and begins contact with an F– (recipient) cell.

Step 2

The pilus enables direct contact between the donor and the recipient cells.

Step 3

Because the F-plasmid consists of a double-stranded DNA molecule forming a circular structure, i.e., it is attached on both ends, an enzyme (relaxase, or relaxosome when it forms a complex with other proteins) nicks one of the two DNA strands of the F-plasmid and this strand (also called T-strand) is transferred to the recipient cell.

Step 4

In the last step, the donor cell and the recipient cell, both containing single-stranded DNA, replicate this DNA and thus end up forming a double-stranded F-plasmid identical to the original F-plasmid.

Given that the F-plasmid contains information to synthesize pili and other proteins (see below), the old recipient cell is now a donor cell with the F-plasmid and the ability to form pili, just as the original donor cell was. Now both cells are donors or F+.

DNA Transfer

In order to avoid transferring the F-plasmid to an F+ cell, the F-plasmid usually contains information that allows the donor cell to detect (and avoid) cells that already have one. In addition, the F-plasmid contains two main loci (tra and trb), an origin of replication (OriV) and an origin of transfer (OriT).

The tra locus contains the genetic information to enable the donor cell to be attached to a recipient cell: the genes in the tra locus code for proteins to form the pili (pilin gene) in order to start the cell-cell contact, and other proteins to get attached to the F– cell and to start the transfer of the F-plasmid.

The trb locus contains DNA that codes for other proteins, such as some that are involved in creating a channel through which the DNA is transferred from the F+ to the F– cell. The OriV is the site at which replication of the DNA occurs and the OriT is the site at which the enzyme relaxase (or the relaxosome protein complex) nicks the DNA strand of the F-plasmid (see Step 3 above).

Although the DNA that is transferred in bacterial conjugation is that present in the F-plasmid, when the donor cell has integrated the F-plasmid into its own chromosomal DNA, bacterial conjugation can result in the transfer of the F-plasmid and of chromosomal DNA.

When this is the case, a longer contact between the donor and the recipient cells results in a larger amount of chromosomal DNA being transferred.

The advantages of bacterial conjugation make this method of gene transfer a widely used technique in bioengineering. Some of the advantages include the ability to transfer relatively large sequences of DNA and not harming the host’s cellular envelope.

Furthermore, conjugation has been achieved in laboratories not only between bacteria, but also between bacteria and types of cells such as plant cells, mammalian cells and yeast.